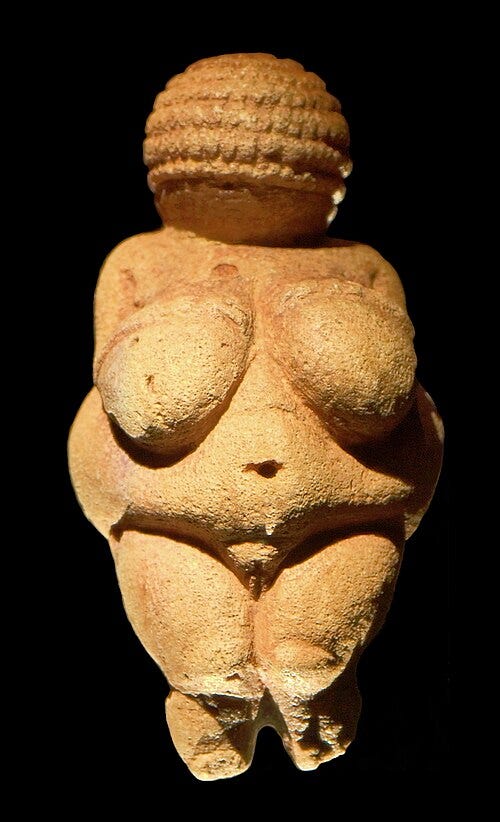

Venus of Willandorf, 23,000 - 28,000 B.C.E. Image credit in footnote1

I have been an outspoken advertising critic since my undergraduate studies, and a social media critic since the Myspace Age. Online influence was a major component of my master's thesis on Communication Ethics. Across any platform, there are unlimited examples of users going "back to basics" for attention, including shock value, non-sequitur, outrage, and the tale as old as time -- sex appeal.

Sex appeal gets taught and studied as a persuasion tactic, but I think it's a little more primal than that. Persuasion convinces through intellectual arguments. Power coerces. Sex appeal deals in physical reactions that are not reasoned arguments, which makes it coercive rather than persuasive, no matter how softly.

The pairing of old attention tactics with gambling impulses in social media has been supremely successful in ways that still bewilder me, and yes, we are all very susceptible, even someone who studied Uses and Gratifications like I did.

Central to the present discussion (and the general theme of my work on Substack) is the artistic element of social media. By virtue of their participation, all participants:

Curate an image

Support ideologies

Influence thought, speech, and action

Make intentional choices within a frame that impact others on and off screen

You, as a producer, are the one choosing what to say, how to edit it, how to show it, what music to add, and, when selling anything (including a self-image or lifestyle), you have to be responsible enough to admit that you chose to do it. The way someone dresses walking down the street is immaterial to their personality or intentions, but the way someone looks in the media that they personally assembled and willfully disseminated to as many people as possible is a part of a considered statement.

Q: How dare you notice what someone took the time to frame, photograph (or in some cases hire a photographer), choose the right outfit, lighting, makeup, scenery, and script to highlight?

A: How could you not?

Millions of people of all sexes and sexualities use sex appeal all the time online. I think when a visceral reaction to my pointing out this facet is an angry one, it's because it posits that a form of coercive power available to people should be off the table on some moral level in some contexts, which, if we are going to condemn the use of coercive power in general, it should be, especially when the product is an in-depth consideration of our values and what constitutes a good life.

This is a particularly sensitive issue for some women, and understandably so, because there is undeniably a tremendous amount of inequality for women in general when it comes to currently-available power structures. To veto sex appeal as a tool is to lose a lot of power for an already power-deficient population. (That we so often reduce sex appeal to mere appearance is another sad by-product of more than a century of advertising, but that's another topic for another time.)

I cannot accept it as misogyny, though, to point out that someone chose to repeatedly include how they look as a prominent feature of how they framed their philosophy project, and that choosing to do so proposes philosophical positions that maybe undercut some of the societal criticisms contained therein.

There's nothing inherently wrong with wearing a bathing suit or ski mask or sexy dress or anything else (actually, Klan robes and SS uniforms come to mind as examples to the contrary). There's also nothing wrong about the human body or nature or beauty or aesthetics in the very least. But the context is a major presentational factor, and unless you have some kind of impairment, you know (hope, even!) that people are going to look when you cultivate visual attention.

An easy example: unless you're at the beach, you generally don't wear a bathing suit to a restaurant or class or a wedding or the supermarket. "Grab a Speedo and head on over to the post office!" Who among you would slip on a ski mask before walking up to the bank counter to negotiate a mortgage?

Silliness aside, there is an important distinction to be made between using sex appeal to sell a product and selling sex as a product, which I made explicit that I didn't think this was a case of the latter, which people also didn’t like for some reason. But when a Western sociocultural context (to which the engagement side of social media certainly belongs) is coupled with the natural, unavoidable fact that reaction to and associations with physical attractiveness are an unchosen part of being alive for most living things, it amounts to Advertising 101 to put some literal skin in the game, which takes on yet another context if that work was potentially stolen.

There is a level egotism involved in this kind of advertising, as well as a cynicism that even excellent work will only go over if the project is using sex appeal on some level. Lots of people believe this and participate in it, but leading with sex appeal makes any other thoughts you wanted to put on offer take a back seat to it. If a picture of a posed, well-lit, attractive person is what you see before you can read the content of an article, that's a classic example of leading with sex appeal.

This is adjacent to political will and arguments about "the way the things are," which imply that a given market (social media in this case) is coercive rather than persuasive. But these arguments also obliterate conceptions of autonomy, choice, personal responsibility, and accountability.

I believe that we always have the agency to choose our actions, even if we very strongly feel differently. In the extreme, we have the word 'martyr' for someone who would rather die than act against their convictions even though survival is a basis for most of our feelings, and that's rare enough that we made a word for it.

If personal agency in this regard isn't a universal truth, it is certainly true when choosing what you present online, which we have identified is an artistic statement.

This is why I found it germane in this case:

Scenario A. is a subtle injection of sex appeal paired with some world-class thinking — a time-tested power move that works as a ubiquitous selling tool across industries regardless of whether or not it is a relevant or moral pairing.

But, in Scenario B., if the written product isn't your work, I don't think it's too big of a leap to scrutinize the concept of what would then be the use of sex appeal as an engagement tactic to sell stolen ideas, especially in an online context where . . .

Scenario C. also happens all the time, in which very unscrupulous people steal sex appeal that isn't theirs as an engagement tactic. This is a decades-old and unfortunately still-prominent practice.

We are almost twenty years from the famous case of pole vaulter Allison Stokke, who was photographed at age seventeen while she was competing at a high school track meet. The picture, stolen (copied and pasted) by strangers, was used as the cover image promoting "hottest athlete" lists on a host of websites and YouTube videos, etc. without her consent or knowledge until an overwhelming number of people on an international scale started quickly invading her personal life. You can’t even google the below interview with her without still seeing examples of the theft of her image. But Allison was an elite competitor and record-holder, and she turned down modeling contracts, morning show segments, and endorsement deals that were offered to her in the name of wanting to be known for her quality as an athlete rather than a sex symbol. I strongly recommend her story:

It's likely very often that Scenario D. also plays out, in which both verbal content and images are stolen, and there are all kinds of repost accounts, revenge porn sites, etc. that have scraped the barrel in this department.

It's bizarre for me (who directed some frank thoughts to what was, at the time of writing, a very small audience of people who I know personally and to whom I had enthusiastically endorsed a total stranger's article on compression culture, which I was compelled to retract upon learning about the plagiarism episode) to have had so many total strangers on either side of what I wrote, and so I now have plenty to empathize with all around.

Katie Jgln deserved credit for her work. Period.

Maalvika hopefully can get to a place where she becomes someone who made a mistake rather than be seen as a permanent, irredeemable, capital P Plagiarist, as it seems some responders would be for (but I am not). Some prominent, official remorse and giving credit due would go a long way to help that. Maybe it already exists by now?

I don't think it's always inherently wrong to employ sex appeal, either, but I also think someone with that level of academic achievement would be able to see how it could easily go sideways and become a disservice (which is the word I used) to any of her original academic projects, which seems to have been the case for many commentators before I spat out a take on my extremely dry, niche, esoteric little corner for essays about art and its non-verbal philosophical implications, which any new readers should now brace themselves to expect.

That article on compression culture is still really great, however, whenever, from whomever it might have come into being. It has certainly given us all a lot to think about.

User:MatthiasKabel, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons